Given the success of Toy Story 2, it was perhaps not surprising that Disney started making plans for a sequel to the even bigger blockbuster success Finding Nemo before that film even hit theaters. Growing tensions between Disney and Pixar during and after Finding Nemo’s release meant that Disney’s original plan was to produce and release the sequel without Pixar’s involvement. After Disney acquired Pixar in 2006, however, all Disney animation came back under the control of John Lasseter, who cancelled the plans for a Disney sequel to Finding Nemo, but kept the idea of a Pixar sequel open. If, that was, writer/director Andrew Stanton could be persuaded to come back on board.

That was a pretty big if. Not only was Stanton already fully booked with work on Wall-E, Toy Story 3 and a live action film, John Carter, he was also less than excited about the concept of churning out sequels for every single Pixar film. Sure, Toy Story 2 had been a critical and financial success, and Cars 2 had been….well, it had made money and sold quite a few toys, but Stanton—perhaps thinking of Cars 2— wanted a better reason for a sequel than “make more money.”

Eventually, Stanton had three reasons: Ellen Degeneres was eager to voice Dory, the memory-hampered fish, again; rather strong hints from Disney executives; and the financial failure of John Carter, which ensured that Stanton would not be tied up with action films for some time. By August 2012, Stanton had started coming up with story concepts; by February 2013, Disney assured eager kids everywhere that yes, yes, little Nemo would be returning in November 2015.

That release date ended up getting pushed back until June 2016, partly because story and production delays on another Pixar project, The Good Dinosaur, had moved that film’s release date to November 2015, and mostly because Pixar and Stanton had something special in mind for Finding Dory: completely reengineering Pixar’s rendering program, Renderman, to improve the depiction of light, and more specifically, the way light moves through water.

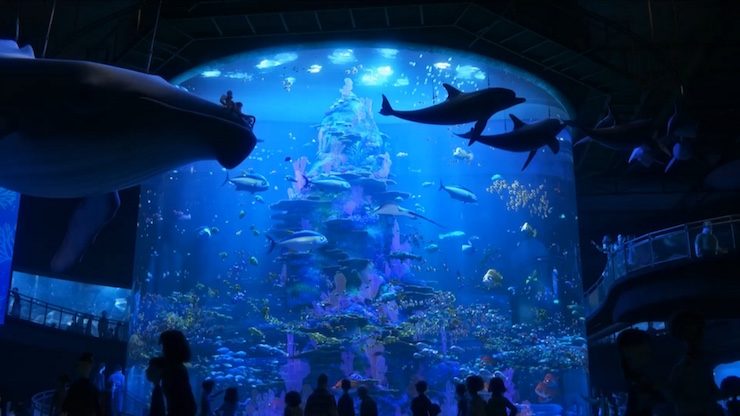

You can tell just how excited Pixar was about this by watching the end credits (which also include additional scenes of Hank, the color shifting octopus, blending into his surroundings), about one third of which are just credits for the Renderman program. The work, however, was worth it: as beautiful as Finding Nemo is, Finding Dory does even better work with underwater light, allowing the light to both subtly guide the story (and Dory) and have the same diffuse look that light does have beneath the water. The software’s showcase moment involves a large indoor aquarium tank lit by multiple light sources both over and surrounding the tank: the new Renderman software allowed Pixar to account for the multiple artificial light sources—in multiple colors, no less—and their diffusion through water.

And as always at Pixar, and especially with sequels, filmmakers faced another problem: story. Finding Nemo had neatly wrapped up the stories of nearly every character except for the Tank Gang—and those characters had never enjoyed the popularity of the little clownfish, Crush the turtle, or Dory. After thinking about it, however, Stanton realized that Dory remained a question mark: where had the little fish with memory issues come from? How had she learned how to speak to whales? Where had she learned her little swimming song? And with that, Finding Dory had a concept, and could move into development.

The film could not focus on only Dory. Little Nemo was far too popular to be left out of the sequel, which naturally meant that Marlin, too, had to come along, whatever his feelings about transoceanic travel. The filmmakers also agreed to feature cameo appearances from other popular Finding Nemo characters, notably Crush. And to ensure that these character appearances wouldn’t make the new film feel like a simple retread of Finding Nemo, the filmmakers decided to set most of the action in a new location: a large aquarium on the California coastline.

As the film opens, little Dory is separated from her doting parents, a rather large issue since Dory has severe short term memory loss, which eventually leads to long term memory loss. Eventually, she meets up with Marlin, leading to what is a rather confusing flashback if for some reason you missed the earlier film, and a completely unnecessary scene if you didn’t, before shifting one year forward, where Marlin and Nemo are both trying to deal with Dory being Dory—clueless, unable to remember almost anything, including important little facts like anemones sting, or where she’s from. Until something starts to jog her memory, and she remembers a single phrase: something connected to her parents.

It’s just enough to send her across the Pacific Ocean to California and a large aquarium there, followed by Marlin and Nemo. The sights and sounds of the aquarium start triggering memories of her past. It all leads to a long exploration of an aquarium/marine park from a fish point of view and one of the most massive Pixar chase scenes yet, involving a truck, an octopus who can make himself nearly invisible, several fish, a beluga, and a whale shark, all even more complicated than I’ve made it sound. Also, Sigourney Weaver becomes Dory’s new friend, in one of Finding Dory’s best running gags. Or swimming gags in this case, I suppose.

It’s entertaining, occasionally sad, and often hilarious, and I have questions. Many questions, nearly all of them about things like water temperature, salinity, and just how clearly a fish can see objects through water, glass AND the windshield of a rapidly moving truck, not to mention just how a beluga whale, using only echolocation, is able to distinguish between annoyed cops chasing down a truck driven by an octopus and regular humans pausing to see a truck driven by an octopus charging down a highway. That’s the sort of thing people pause to watch, whale, is what I’m telling you.

I would also like to know why, exactly, so many otters are willing to risk Death By Getting Squished On a Highway just because a cheerful blue fish suggested this. Ellen DeGeneres is amazingly charismatic, yes, but this charismatic? And perhaps I’m just becoming too much of a curmudgeon as I age, but as touching as the reunion is between Dory and her parents in that kelp forest, I could not help thinking that, UH, TROPICAL FISH PARENTS, POSSIBLY A COLD KELP FOREST IS NOT THE BEST PLACE TO WAIT FOR YOUR DAUGHTER, primarily because, given that Dory was sucked into quarantine more or less by accident, and wasn’t actually sick, the most logical thing to do would have been to wait for Dory back in their large tank once Dory had been medically cleared, BUT ALSO SINCE YOU ARE TROPICAL FISH, THE COLD KELP FOREST IS NOT WARM ENOUGH FOR YOU AND YOU WILL DIE frankly I am ASTONISHED that Dory turned out as well as she did.

That’s beyond the various genuine plot holes, with at least one caused by a mild confusion in marine biology: how did Destiny, a whale shark, with emphasis on shark, manage to teach Dory whale language given that—to repeat—Destiny is a shark, not a whale. On a similar note, why did Dory need to learn how to talk to whales at all, given that nearly all of the animals in this film—one dimwitted bird aside—have no problems communicating with each other or understanding Signorney Weaver?

And apart from their popularity and the need to sell toys, how much did Marlin and Nemo, standouts in the last film, really need to be in this one? At times, their scenes almost feel like unwanted intrusions into Dory’s tale—though to be fair, I suspect that Dory would have forgotten them, too, had they not trekked across the Pacific Ocean to help her and remind her what she was looking for, and thus, she would not have been able to return to the Great Barrier Reef.

But all that aside, and some very Scary and Sad moments where Dory is All Alone in a Very Cold Ocean, this is for the most part a funny film, with a disability message I can embrace: you can do things your very own Dory way. And you might even, against all odds, succeed. Finding Dory avoids the simple answer of a magical cure: from beginning to end, Dory suffers from short term memory loss, and never does manage to cure this, even after bits and pieces come back to her. She even has to be reminded about the things she is remembering. And she needs help—though that’s partly because, all else aside, she’s also a fish who needs water to live, which makes moving through the various tanks in the Marine Life Institute rather difficult. When she finds herself alone again, she is terrified—she has, after all, just had a rather traumatic experience, and she’s not at all confident in her own abilities—understandably so. And yet, she manages to pull herself together, without help this time. Give her the tools she needs, and she can find her parents and free a truck load of fish.

Add in that this was only the third out of seventeen Pixar features with a female protagonist, plus a curmudgeonly octopus capable of disguising himself as pretty much anything, and some sea lions, and Finding Dory has a lot to love. Let’s face it, put Idris Elba in pretty much anything, and I’m happy. I’d be even happier if Finding Dory had more of him, especially since I’m a sucker for California sea lions, but just a few words from him goes far to reconcile me to this film.

Audiences were equally reconciled. Finding Dory was an enormous success, bringing in $1.028 billion at the box office, making it Disney’s third film of 2016 to pass the $1 billion mark, after Zootopia and Captain America: Civil War. It would later be joined in this achievement by Rogue One, allowing Disney to be the first Hollywood studio to release four films each earning over $1 billion at the box office in a single year, and also allowing Disney to take the top five highest grossing films in the world spot for 2016; it was the first year since 1913 where any Hollywood studio was able to dominate all five top spots on the box office list. (The Orlando Sentinel, which covers Walt Disney World news, found this very exciting.) Disney did not quite have the ability to create and sell a toy octopus capable of completely blending into its surroundings, but they could and did sell plush octopus toys, as well as new stuffed animals based on baby Dory (this one is adorable), Bailey the beluga whale, and the otters. Disney also launched a new line of Finding Nemo/Finding Dory merchandise including mugs, clothing, tote bags and more, incorporating elements from the sequel.

It would all seem to lead to plans for a third sequel—one possibly based on finding happiness for Hank the Octopus, if I may be so bold as to make the suggestion. With “seem” as the key word here. In 2016, despite the fact that three more sequels were already either in production the (Cars 3 and Incredibles 2) or planned (Toy Story 4) Pixar suddenly announced a reversal to their GO SEQUELS GO plans, stating that after Toy Story 4, all Pixar films would be originals.

Which means that, barring a reverse of the reversal, or a television show, Finding Dory may be our last look at those fish from the reef.

At least we left them in a happy place.

Next month, the next sequel: Cars 3.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

This film was a parenting milestone for me: The first Pixar movie that my son, now a teenager, declined to see. He insisted that he’d never liked Finding Nemo that much in the first place, and he felt let down by The Good Dinosaur, but I think it was mostly just teenagerdom. I don’t think he’s seen a Disney or Pixar film since. My wife and I saw it by ourselves in the theater, and while we liked it fine, it wasn’t particularly special for us.

Hank is technically a septopus, having only 7 tentacles. I don’t remember if it was addressed in the film itself, but I know from the bonus features that 7 tentacles were all that they could successfully render and control at one time, 8 was just one too many for the computers to handle.

@2 — And in It Came from Beneath the Sea, Fisherman’s Wharf is attacked by a hextopus because Ray Harryhausen couldn’t do stop-motion animation on eight tentacles.

On the one hand, this movie does feel like the textbook definition of an unnecessary sequel; on the other hand, in a lot of ways I think I like it better than Finding Nemo.

This was a better sequel than I expected. I didn’t quite like the decision to make Dory’s memory issues an individual disability rather than a species trait as I always assumed it was, but I can see how that’s useful for presenting disability in an empowering way. I did feel the film cheated a bit by having her remember long-term stuff when it was plot-convenient, but I guess it was hard to make a whole film about a protagonist with no long-term recall at all, since she couldn’t write stuff down like the guy in Memento.

@2/LazerWulf: Since “octopus” comes from Greek, I think the term would be “heptopus.” Anyway, there’s precedent — Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion giant octopus in It Came from Beneath the Sea in 1955 had only six tentacles since it would’ve taken too much time to animate eight. Harryhausen jokingly called it a “sixtopus,” though it would’ve more properly been “hexopus,” I guess.

@4/CLB: I’ll concede to your knowledge of word origins as to whether hept-/sept- is the correct form, but “septopus” is the word they used in the Bonus Features, and IMO, is the catchier of the two words. (“See You in Heptember” just doesn’t quite have the same ring to it, don’t you think?)

Finding Nemo was totally forgettable for me. (Might be different all these years later, now that I have kids.) Finding Dory I found to be both emotional and hilarious, and only slightly more memorable than the first.

This was a lot of fun, one of the rare sequels that ranks right alongside the original.

I found Finding Dory visually less interesting than Finding Nemo, since they don’t travel through many different oceanic zones. However, I think I enjoyed FD more overall. The Monterey Bay Aquarium is one of my favorite places on the planet, and I live 3000 miles away from it, so it was great to get to go back to it courtesy of Pixar. (I know, the aquarium in the movie is something of a composite of a few different aquariums…but there’s a lot of the Monterey Bay Aquarium there.) And for me, Sigourney Weaver’s voice steals the show.

In terms of the parent/child feels: I found the one visual of Dory’s home with all the many years’ worth of shell pathways pointing the way to be an extremely evocative picture of parental love. It sticks with me more than all the fatherly worry in Finding Nemo.

I remember enjoying this one a lot more than I thought I would. I am really skeptical of sequel-itis (he says as he hopes against hope that Incredibles 2 manages to shine) however I really liked Finding Dory. I suspect it definitely helps if you don’t know much about fish temperatures (as our reviewer apparently did) because it never occurred to me about which fish would live in which zones.

I think in the end, the voice acting sells these things for me more than just about anything else.

Marlin and Nemo definitely felt like tag-alongs in this one, all of their scenes pretty much filler while I waited for the story to get back to what Dory was doing. I guess as you say, someone had to lead her home again, but couldn’t they have been doing something more important than just following in her wake?

@9: I have… guarded hope for Incredibles 2. While Pixar’s record on sequels isn’t perfect, the Toy Story series managed to build on itself to make each new episode deeper; if Pixar can manage even half that for Incredibles 2, it ought to be OK.

I knew I wouldn’t love this film as much as Finding Nemo, because no film could ever be as perfect and glorious as Finding Nemo. I watched it anyway, feeling obligated to as a marine biology educator. It still managed to disappoint me. My favorite part was the short before it with the adorable baby sandpiper-type-bird.

Oh, the animation is gorgeous — as it ruddy well should be, 13 years of technological innovation after the beautiful Finding Nemo. But as Saavik said, it spends far less time in the ocean and more time in an aquarium. I love aquariums. Working in an aquarium has long been my dream job, temporarily attained years ago and still desired. But only because it’s slightly more attainable that a job in the ocean, which is where I would rather be and what I would rather watch.

The inaccuracies felt like a much bigger deal because they’re much more central to the plot. As Mari says, whale sharks aren’t whales, a whale’s echolocation really doesn’t work like that, and releasing a load of assorted marine life into a part of the ocean they’re not native to is a terrible idea because they’re all likely to either die or, if they thrive and breed, become invasive species. Furthermore:

~The oceanography is wonky. Real-life sea creatures can and do (unintentionally) travel from the Great Barrier Reef to Sidney on the East Australian Current, as happened in Finding Nemo, though most of them can’t travel back. But the great ocean gyres are clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the southern Hemisphere. To go from the Great Barrier Reef to California without passing through Antarctic and Arctic waters, a turtle would have to swim against the current much of the way even if he could catch the eastbound Equatorial Countercurrent for part of it. Maybe they do that, but it sounds like a ruddy arduous journey.

~Loons don’t run around on the ground like robins. Loons have short legs very far back on their bodies, ideally positioned for swimming but nigh-impossible to stand on and very hard to walk with.

~Regal Blue Tangs don’t live in the open ocean, so it’s a weird tank to put them in. And until shortly after the film debuted, they didn’t breed in captivity.

~Fish don’t “gotta blink,” as Dory said. They lack eyelids. A whale shark would probably not have been fed baitfish like those Dory hid among, but eh, Plot Reasons.

~Belugas aren’t tropical, the squid in the kelp forest is an open-sea species, an octopus can’t survive out of water that long, and marine fish aren’t likely to pass unharmed through various receptacles of fresh water, especially in a janitor’s mop bucket. But I’ll write all of that off to Rule of Cool, and also Plot Reasons.

~Probably other things I’m forgetting, because I watched it once instead of many times like Finding Nemo.

I’ve read a number of articles opining on how the film portrayed various characters’ physical and mental disabilities — some positive, some negative, relatability and played-for-laughs hurtfulness. I was especially bothered that Hank’s seemingly-implied PTSD (“very bad memories”) about the ocean and desire to be far away from it got steamrollered in Dory’s quest to escape, with her calling him “heartless” and suchlike.

I haven’t worked in a full-blown aquarium since 2013, so I don’t know if Finding Dory influenced public feelings about them. It never seems to be mentioned at the coral reef tanks at the paleontology museum where I still volunteer and kids still yell “IT’S NEMO!” (I like to point out the yellow tangs and masked longnose butterfly fish also found in Finding Nemo). It has increased the demand for regal blue tangs in defiance of its own message, because boneheads will again be boneheads.

This was the first Pixar movie where I really felt like the patented sad-pixar-movie-scene felt manipulative rather than effective. This is more a reflection on me than the movie, though, because nothing in Finding Dory is inherently more manipulative than Toy Story.